Telling the story of Rohingya statelessness in a new way

Built over the past four years in a movement within Rohingya communities, and allies in partnership with the CAP, Medecins Sans Frontieres and many other collaborators.

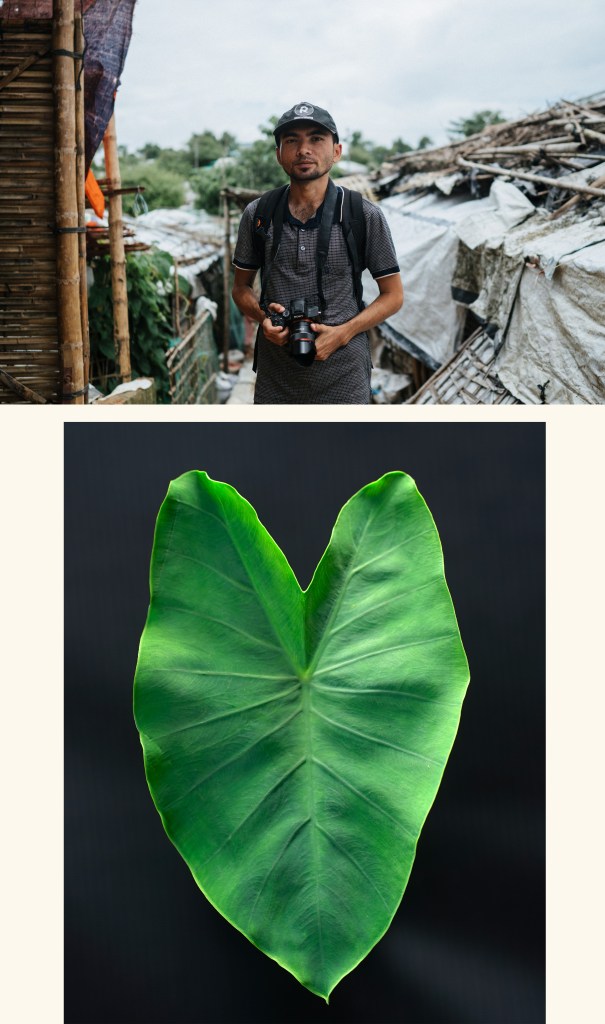

The Taro leaf is growing as a symbol in the Rohingya advocacy movement. It comes from the proverb Hoñsu Fathar Faaní (water on a Taro leaf), which speaks to the way water sits on a Taro leaf like its floating, and when the wind blows it rolls off, leaving no mark.

“This is what statelessness feels like, because in Arakan our existence is being erased, and no matter where we live we cannot make a mark, its difficult to get our documents, practice culture and build a life. It feels like we are floating above the land, even gravity is against us. But for Rohingya, existing is resisting, we need to keep living our lives, telling our stories, and continuing our legacy.” – Rohingya leads in the Creative Advocacy Partnership (CAP).

The word statelessness is a political label that has been imposed on the Rohingya, although it plays a role in advocating for rights it’s a term that brings shame for many in the community. Besides this the word has perhaps lost some effect, unfortunately we all become desensitised to these terms, so the Taro leaf aims to re-introduce this story in a different way; in community language, and through a symbol that speaks more to the experience of statlessness. This aims to move people and build care and allyship in the broader public.

“This word has been put on us, we are not stateless, we have a state, but we were pushed off that state. In Rohingya Statelessness is ‘basha’ which is a dirty word meaning you are floating, you have nothing, no roots anywhere. I’d rather say I am Rohingya, Indigenous to Maynmar”-Ruhul.

The symbol first emerged while co-designing the Meeras Pavilion with Rohingya in Sydney, Malaysia and Kutupalong. During a community conversation one man used Hoñsu Fathar Faaní to describe the feeling of statelessness. Then when Noor Azizah voiced her frustration about the lack of visibility in the Rohingya rights movement, the Taro leaf felt like a powerful tool that could help to build solidarity amongst advocates and allies.

“We have nothing fancy to give, we dont have watermelon emoji’s, a loud community or fancy shirts to offer, most of our community members are rebuilding their lives post-resettlement” – Noor Azizah

Over the past 3 years the CAP has been supporting Rohingya communities to develop and spread the Taro Leaf through storytelling and creative projects.

Watch the story of the Taro Leaf:

Developing the symbol with artists in

Kutupalong refugee camp

In June CAP members Tasman, Arunn, Victor partnered with 10 Rohingya artists and 10 kids in Kutupalong (the largest refugee camp in the world) – developing the Taro leaf symbol and launching it internationally through Rohingya voice and craft.

Through two weeks of storytelling and collaborative making we created 8 versions of the Taro leaf in different crafts (woodcarving, basketry, net weaving, embroidery, ceramics, food and photography) as well as an animated poem and Kyssa (folktale).

Powerful words from the artists

Meets the artists and their works

Nurul Islam

Bamboo and Nylon Weaving

Nurul first learned weaving in 1991 as a refugee in Moricha, Bangladesh, and then again upon returning to Myanmar — only to be expelled in 2017. “My father had some skill in weaving, so I tried to learn from him. He used to work on commission pieces. I wanted to carry that on.”

His work is a message to the world: “We have no land under our feet, but with the help of others, we can keep our culture alive — and one day regain our freedom. Unless we return to our homeland, our culture will fade. Without art, we are not fully Rohingya. When water falls on a taro leaf, we hope it leaves a mark. This is our mark — especially for when we return.”

Nuru Sabar

Fish Net Weaving

Nuru’s curiosity led her to learn different craft practices from everyone around her — farmers, makers, weavers. “I asked them to teach me. I learned from my grandparents, who used basketry to make all kinds of farming tools. Since I had no elder brother, I learned everything — even ploughing. My husband was a refugee in 1992. He taught me how to make stools. And I kept learning.”

She now sees this work as an act of cultural preservation. “If we don’t pass this on to our children, it will disappear — and with it, our Rohingya name. This is how I keep my grandparents alive. This is how I leave my mark. Like water on a taro leaf, nothing remains unless we make an effort. If we lose our culture, we disappear.”

Mohamed Kolim

Wood carving

Kolim began woodworking at age 10 in Arakan, learning from a local carpenter to survive. “We started this work out of necessity, to put food on the table, many people buy my furniture for weddings, I also make lots of baby cradles.” Through carving the taro, Kolim shares a message: “Our life is like water on a taro leaf, we have no ground beneath us, no place to stand. But by showing this publicly, across the world, we leave a mark that cannot be thrown away.”

Senu Anara

Embroidery

Senu trained in weaving through a vocational program in Myanmar when she was 23 years old. She is used to making lungis, scarves, pillow covers, and bedsheets. Her embroidery carries both cultural memory and quiet resistance.

“We never thought the Rakhine and Burmese governments would drive us away, the taro leaf is our document, and we are the water. The leaf remains in Myanmar, and like water, we’ve been forced to flow elsewhere. If we show this to the world, maybe our mark will remain.”

Kali Kumar Rudro & Bishi Bala Rudro

Ceramics

Kali learned pottery from his father, and Bishi Bala from her in-laws after marriage — continuing a craft that spans generations. From pots to animals, jugs to toys, they shape clay with memory and meaning.

“We live under tarpaulin sheets because we have no land, no country,” they say. “That’s what makes us stateless. But by working together — with people from different places — we create something joyful. That’s what we like about this project.”

Rayhana Begum

Rohingya Cuisine

Rayhana’s love of cooking began with her mother and sisters. After marriage, faced with financial hardship, she and her husband opened a small betel nut stall at their home. They hired a cook — and Rayhana learned by watching, eventually becoming a skilled chef herself.

“I encourage all Rohingya women to learn and become skilful, so they can support their families. Our dishes reflect a deep and rooted culture tied to Myanmar. Through this food, I hope the world sees that — and helps us return. We are like dust on the river’s surface — always moving. But we are human, and we deserve human rights. We deserve to be recognised as an ethnic group of Myanmar.”

Sahat Zia Hero

Photography

Sahat began photography in Myanmar in 2014, first photographing football games. But after the 2017 military violence forced him to flee to Bangladesh, his focus shifted. He began documenting life in the refugee camps — not just to bear witness, but to make the world feel.

An award-winning photojournalist, Sahat now runs Rohingya phographer, a global platform amplifying Rohingya voices through photography.

“The taro leaf in my photo shows the world that our crisis continues — that we are still here. The world is big enough to carry us, but we are treated like water on a taro leaf: never given a place to rest. I want the world to know that Rohingya people are human beings. We exist. We deserve peace, knowledge, and dignity — just like everyone else.”

Asma Nayim Ulla

Poetry

Asma began writing poetry as a way to process grief and displacement after fleeing Maungdaw. Now based in Sydney, she uses language to reclaim identity and voice — drawing on the rhythms of Rohingya storytelling, prayer, and memory.

“In our culture, women carry pain quietly — but poetry lets me speak. It lets me leave a mark, even when so much has been taken. Each word becomes a thread tying me back to home. We’ve lost our land, but we haven’t lost our voice — and that’s what I want the world to hear.”

Mohamed Faruk and 10 Rohingya kids

Illustration

Faruk was the lead illustrator, a self-taught artist, who also aspires to be a photographer. His earliest inspiration came from cinema sign painters in Maungdaw. “I watched them draw heroes and heroines. I didn’t have pencils or paper, but I drew anyway — a rabbit was my first. The face looked right. The body didn’t. We didn’t have birthday parties. So I don’t know how old I was, maybe 10 or 11 when I started. I never did a course, but I learned by doing. Art is how I show the world who we are — that we are alive, that we have culture, that we still dream.” 10 other Rohingya kids also collaborated for two days creating additional frames and illustrations around Faruks work.

Mohammed Yakub

Storytelling

Yakub grew up surrounded by stories — first told by his mother and elders, then shared by him with children in the camps. “I’ve been storytelling since I was young, always with a focus on education, morals, and the culture we carry.” Now Yakub is a trained community journalist and producer. For the symbols project, he presents Nadtwa Fata — The Dancing Leaf — a story drawn from memory and reflection on his situation. “A journalist can destroy a country — or help rebuild it. I want to be a representative of Rohingya culture. If I can show the world that we also belong to Golden Arakan, maybe they will help us return.”

Sofaida and the Water : A Rohingya Kyssa

by Mohamed Yakub

(Adozja Nati okkolore kissa hoor – tells a story to her lovely grandchildren)In a village called Tailla Fara, which was separated by a silver-colored river, there grew a garden of taro leaves. Their hearts were wide, green, and open to the sky. Among them lived a small leaf named Sofaida. Sofaida had one dream: to hold something of the world—rain, sunlight, or stories whispered by the wind.

When the monsoon came, Sofaida stretched herself as wide as she could, ready to catch the sky’s sorrow. But the rain slipped off her every time—drip, drop, and gone.

The villagers came and said:

“Sofaida, help us catch the rain for drinking and washing.”

Sofaida tried, but the water slid right off without leaving a mark. Some villagers shook their heads.

“Sofaida is useless,” they muttered. “She cannot carry anything.”

Sofaida curled in on herself, ashamed.

“Maybe I was never meant to matter,” she thought.

But then, a myna bird and her mate came. They gathered the leaves—including Sofaida—to build a nest for laying their eggs. They layered them carefully side by side, edge to edge, and shaped them into a shallow bowl. After the eggs were laid, the shallow-shaped nest came into use again.

When the rain came again, the nest held it.

Not a drop escaped.

The birds and insects drank, washed, and the collective of taro leaves became a swimming pool for them.

Sofaida looked around and saw herself—not alone, but part of something bigger: a nest of leaves that held the sky.

And the old storyteller, Bura Dadi, said: “This is how we survive—not alone but together.

We may not hold much on our own, but joined, we carry rivers.”

She turned to her grandchildren and added:

“Did you not hear the proverb:

Sollukor Naw Faarotun solee, besollukor Naw dhoriyad tun’o no solee—

A boat of unity sails on mountains,

A boat of disunity does not even sail in a river.”

Transportation is simple: if we are united, we can cross mountains hand in hand. If we are disunited, we cannot even cross rivers—even with a boat.

From that day, the taro leaf became more than a plant.

It became a sign of unity, survival, and quiet strength.————————————————————————————–

Moral

Alone, a leaf sheds water.

Together, they can hold the rain.

The Rohingya carry each other—and that is how they endure.

Exhibition in Kutupalong

The project finished up with an exhibition in the camp, which was a powerful moment of truth telling and celebration, with Rohingya food, music and speeches from the artists presenting their work and stories to families and community leaders as well as local and international staff at the MSF run hospital.

Meeras Pavillion

The Taro Leaf project has grown into something even bigger! Meeras is a large public artwork, made from 16 arching Taro Leafs that create space to celebrate Rohingya stories and bring diverse communities together. It was on display in Sydney in 2025 and we’re planning a tour to other places. Read more here.

Photo Credits

Photos on this page by Victor Caringal, Sahat Zia Hero and Tasman Munro.